The Central Library provides a critical lifeline for people without access to a computer.

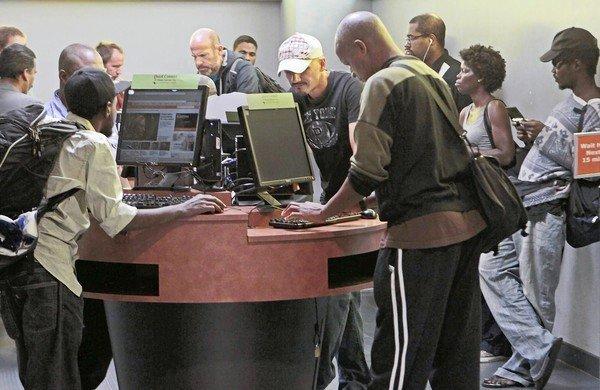

People wait in line for 15 minutes for

a computer at the Central Library. (Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times /

October 16, 2012)

|

Murray Carter, 56, is living a life without luxury. He's out of work. He

sleeps at the Weingart Center on skid row.

He's hoping for a job as a cook. He needs to go online to find one. But he's worlds away from affording either a computer or Internet access.

Well before the Central Library opens at 10 a.m., Carter waits out front to get in and grab a computer terminal.

Toni Albert, 23, of East L.A. takes night nursing classes at community college. Her mom helps by looking after her baby. But Albert also needs a computer and one's out of reach for now. So she waits, too, holding 7-month-old Zariyah to her chest.

A few years ago, L.A.'s libraries cut their hours — hit, like everywhere else, by budget cuts.

To those clinging to the 73 branches as lifelines and safe houses, the cuts were crushing blows.

Live on the street and you have to be very wary. Breathe deeply and relax, bad things happen. In the library, you let down your guard for a while — use the sinks and the toilets, gaze up into the rotunda, watch TV or play animated slots in the ever-crowded, subterranean computer center.

"During the summer, everybody comes in here to cool off. And during the winter, people come in out of the rain. It's a safe place to be," said Viola Castro, a library clerk at the center's help desk.

Jeri Emmett Laird, 76, has striking snow-white hair and icy blue eyes, and she used to have a house above Sunset Boulevard. In the 1960s, Laird wrote a memoir about being a Playboy bunny. She sang in an antiwar group "Mother's Quaker Oats and Her Peaceful Marching Band." She wrote episodes of "The Fugitive." But with time, the firm foundations of her life began to slip. Her husband died. Her son died. She was diagnosed with breast cancer. Then bedbugs invaded the Koreatown building where Laird and her daughter had lived for years. They got rid of everything — mattresses, books, computers. "We went to the 99 Cent store and bought new outfits and changed in the parking lot," she said. They started over at the Alexandria Hotel downtown. And the Central Library became Laird's off-site office. She's writing a book, she says.Near her, one man hunches over a war game. Another stares at a screen full of blonds.

Anyone with a library card can reserve a terminal for an hour. Those without cards wait in a line for machines parceled out in 15-minute stints. The 15-minute line's there all day long.

Some saw the mayor outside the library the other morning, when he showed up to announce extended library hours. But while the news conference stretched on, the library stayed shut — an hour and a half later than usual. Those who needed it most waited outside impatiently, ever more anxious to get in.

He's hoping for a job as a cook. He needs to go online to find one. But he's worlds away from affording either a computer or Internet access.

Well before the Central Library opens at 10 a.m., Carter waits out front to get in and grab a computer terminal.

Toni Albert, 23, of East L.A. takes night nursing classes at community college. Her mom helps by looking after her baby. But Albert also needs a computer and one's out of reach for now. So she waits, too, holding 7-month-old Zariyah to her chest.

A few years ago, L.A.'s libraries cut their hours — hit, like everywhere else, by budget cuts.

To those clinging to the 73 branches as lifelines and safe houses, the cuts were crushing blows.

Live on the street and you have to be very wary. Breathe deeply and relax, bad things happen. In the library, you let down your guard for a while — use the sinks and the toilets, gaze up into the rotunda, watch TV or play animated slots in the ever-crowded, subterranean computer center.

"During the summer, everybody comes in here to cool off. And during the winter, people come in out of the rain. It's a safe place to be," said Viola Castro, a library clerk at the center's help desk.

Jeri Emmett Laird, 76, has striking snow-white hair and icy blue eyes, and she used to have a house above Sunset Boulevard. In the 1960s, Laird wrote a memoir about being a Playboy bunny. She sang in an antiwar group "Mother's Quaker Oats and Her Peaceful Marching Band." She wrote episodes of "The Fugitive." But with time, the firm foundations of her life began to slip. Her husband died. Her son died. She was diagnosed with breast cancer. Then bedbugs invaded the Koreatown building where Laird and her daughter had lived for years. They got rid of everything — mattresses, books, computers. "We went to the 99 Cent store and bought new outfits and changed in the parking lot," she said. They started over at the Alexandria Hotel downtown. And the Central Library became Laird's off-site office. She's writing a book, she says.Near her, one man hunches over a war game. Another stares at a screen full of blonds.

Anyone with a library card can reserve a terminal for an hour. Those without cards wait in a line for machines parceled out in 15-minute stints. The 15-minute line's there all day long.

Some saw the mayor outside the library the other morning, when he showed up to announce extended library hours. But while the news conference stretched on, the library stayed shut — an hour and a half later than usual. Those who needed it most waited outside impatiently, ever more anxious to get in.

No comments:

Post a Comment